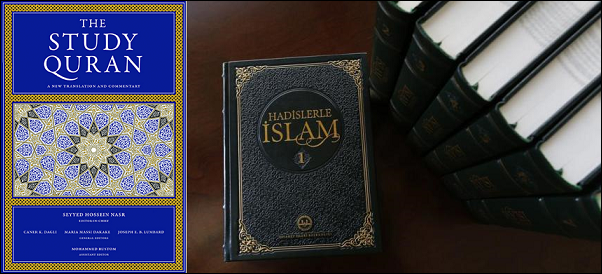

[ by Charles Cameron — SH Nasr’s The Study Quran and the Diyanet collection of ahadith ]

.

**

In a recent post I quoted President Sisi‘s speech calling for “a revolution” in Islamic thinking about “that corpus of texts and ideas that we have sacralized over the centuries” and which is now “antagonizing the entire world”. I would like to bring your attenbtion here to two publications which may well provide support for such a rethinking: SH Nasr’s The Study Quran and the Diyanet collection of ahadith

**

The Study Quran:

I have seen some of the proofs of this Quran, and it strikes me that once it is published (in Fall this year) it is likely to be the resource of record for anyone lacking in depth Arabic language skills and knowledge of Islamic thought across history. Superb, and very auspiciously timed.

From their prospectus:

In The Study Quran, renowned Islamic scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr and a team of editors address the deeper spiritual meaning of the Quran, the grammar of difficult passages, legal and ritual teachings, ethics, theology, sacred history, and the place of various passages of the Quran in Muslim life.

For the first time, both Muslims and scholars will have a clear and reliable resource for looking up the history of interpretation for any passage in the Quran—together with a new, accurate English translation.

From the book itself:

The Quran is the constant companion of Muslims in the journey of life. Its verses are the first sounds recited into the ear of the newborn child. It is recited during the marriage ceremony, and its verses are usually the last words that a Muslim hears upon the approach of death. In traditional Islamic society, the sound of the recitation of the Quran was ubiquitous, and it determined the space in which men and women lived their daily lives; this is still true to a large extent in many places even today. As for the Quran as a book, it is found in nearly every Muslim home and is carried or worn in various forms and sizes by men and women for protection as they go about their daily activities. In many parts of the Islamic world it is held up for one to pass under when beginning a journey, and there are still today traditional Islamic cities whose gates contain the Quran, under which everyone entering or exiting the city passes. The Quran is an ever present source of blessing or grace (barakah) deeply experienced by Muslims as permeating all of life.

Inasmuch as the Quran is the central, sacred, revealed reality for Muslims, The Study Quran addresses it as such and does not limit it to a work of merely historical, social, or linguistic interest divorced from its sacred and revealed character. To this end, the focus of The Study Quran is on the Quran’s reception and interpretation within the Muslim intellectual and spiritual tradition, although this does not mean that Muslims are the only intended audience, since the work is meant to be of use to various scholars, teachers, students, and general readers. It is with this Book, whose recitation brings Muslims from Sumatra to Senegal to tears, and not simply with a text important for the study of Semitic philology or the social conditions of first/seventh-century Arabia, that this study deals.

**

The other publishing venture of great interest in this context is Turkey’s Diyanet project for a contemporary selected edition of the Hadith.

Emran El-Badawi, co-director of the newly formed International Qur’anic Studies Association, told the Christian Science Monitor in 2013:

Change is certain to come to the Islamic world, not just to the streets of Cairo or Istanbul but deep within Islam’s religious tradition as well. The Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs, called the Diyanet, recognizes this with its seven-volume revision of the Hadith – which is the source of Sharia law and second only to the Quran.

Thousands of the prophet’s sayings and traditions were circulated and eventually collected in the centuries after his death in 632. The sheer size of Hadith collections and their archaic 7th century Arabian context have made the texts too intractable for many Muslims today. This is the challenge which the six-year Turkish Hadith project, with its selections and interpretive essays, seeks to overcome.

The central issue surrounding the Hadith, as with other foundational religious works such as the Bible, is whether it should be read literally or in a historical context and for its inspired message. A literal reading, for instance, may seek to justify medieval practices like severing the hands of thieves or allowing underage marriage. An inspired interpretation would see them as historical practices absent the kind of rule of law that democracies like Turkey have today.

The question for Turkey’s new multi-volume set is whether its contemporary interpretations can be widely appreciated by the Islamic community, or whether they will be considered too avant-garde – the fate of previous modern interpretations.

Elie Elhadj, in his post A Turkish Martin Luther: Can Hadith be Revised? on on Joshua Landis‘ Syria Comment blog wrote in 2010:

The Indian Islamic thinker Muhammad Ashraf observed that it is curious that no caliph or companion found the need to collect and write down the Hadith traditions for more than two centuries after the death of the Prophet (Guillaume, Islam, 1990, 165). Ignaz Goldziher concludes “it is not surprising that, among the hotly debated controversial issues of Islam, whether political or doctrinal, there is none in which the champions of the various views are unable to cite a number of traditions, all equipped with imposing Isnads” (Goldziher, Muslim Studies, 1890, Vol. II., 44). John Burton observes, “the ascription of mutually irreconcilable sayings to several contemporaries of the Prophet, or of wholly incompatible declarations to one and the same contemporary, together strain the belief of the modern reader in the authenticity of the reports as a whole” (Burton, An introduction to the Hadith, 1994, xi).

Leaders of Turkey’s Hadith project say successive generations have embellished the text, attributing their political aims to the Prophet Muhammad (BBC, February 26, 2008).

And Tom Heneghan, Religion Editor for Reuters noted in 2013:

The collection is the first by Turkey’s “Ankara School” of theologians who in recent decades have reread Islamic scriptures to extract their timeless religious message from the context of 7th-century Arab culture in which they arose.

Unlike many traditional Muslim scholars, these theologians work in modern university faculties and many have studied abroad to learn how Christians analyse the Bible critically.

They subscribe to what they call “conservative modernity,” a Sunni Islam true to the faith’s core doctrines but without the strictly literal views that ultra-orthodox Muslims have been promoting in other parts of the Islamic world.

As to its likely influence, in Egypt and thus (I infer) on Sisi’s project, Heneghan offers this hint:

“Among intellectuals in Egypt, there is a welcome for this new interpretation which they think is very important for the Arab world to be exposed to,” said Ibrahim Negm, advisor to Egypt’s grand mufti, the highest Islamic legal authority there.

**

I haven’t seen any reference as yet to the preparation of an English translation.