[ by Charles Cameron — a follow up to my earlier post Of dualities, contradictions and the nonduality, with its Yogi Berra / Andrei Tarkovsky DoubleQuote ]

.

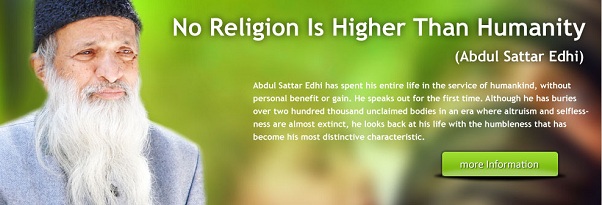

Abdul Sattar Edhi is the subject of a Telegraph piece I read today:

**

Short form, excerpted from this article:

Born in 1928 and thus now more than eighty years old, Abdul Sattar Edhi “lives in the austerity that has been his hallmark all his life.”

60 years ago, he stood on a street corner in Karachi and begged for money for an ambulance, raising enough to buy a battered old van. … Gradually, Mr Edhi set up centres all over Pakistan. He diversified into orphanages, homes for the mentally ill, drug rehabilitation centres and hostels for abandoned women. He fed the poor and buried the dead. His compassion was boundless. [ … ]

Just 20 years old, he volunteered to join a charity run by the Memons, the Islamic religious community to which his family belonged. At first, Mr Edhi welcomed his duties; then he was appalled to discover that the charity’s compassion was confined to Memons. He confronted his employers, telling them that “humanitarian work loses its significance when you discriminate between the needy”. So he set up a small medical centre of his own, sleeping on the cement bench outside his shop so that even those who came late at night could be served. [ … ]

Mr Edhi placed a little cradle outside every Edhi centre, beneath a placard imploring: “Do not commit another sin: leave your baby in our care.” … Once again, this practice brought him into conflict with religious leaders. They claimed that adopted children could not inherit their parents’ wealth. Mr Edhi told them their objections contradicted the supreme idea of religion, declaring: “Beware of those who attribute petty instructions to God.”

**

All that is by way of context for the three paras that really interest me here, which describe the impact of his non-sectarian, non-partisan — one moght almost say non-dual — approach to the fractured world in which we all live:

Mr Edhi did not distinguish between politicians and criminals, asking: “Why should I condemn a declared dacoit [bandit] and not condemn the respectable villain who enjoys his spoils as if he achieved them by some noble means?”

This impartiality had its advantages. It meant that a truce would be declared when Mr Edhi and his ambulance arrived at the scene of gun battles between police and gangsters.

“They would cease fire,” notes Mr Edhi in his autobiography, “until bodies were carried to the ambulance, the engine would start and shooting would resume.”

**

**

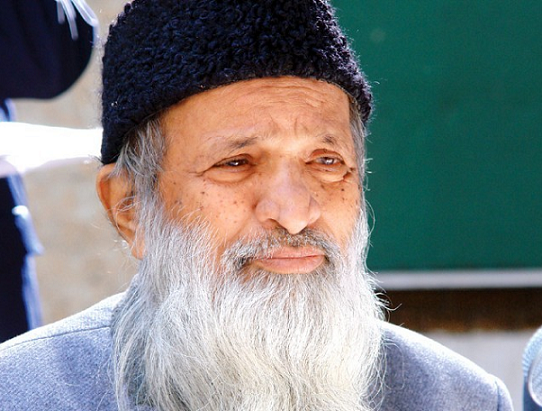

There’s the narrative itself, there’s the face so beautifully carved by the living of that narrative — and there’s the insight which propels both.

For the current work of the Edhi Foundation, see here: EF provides free treatment to 3,104 patients