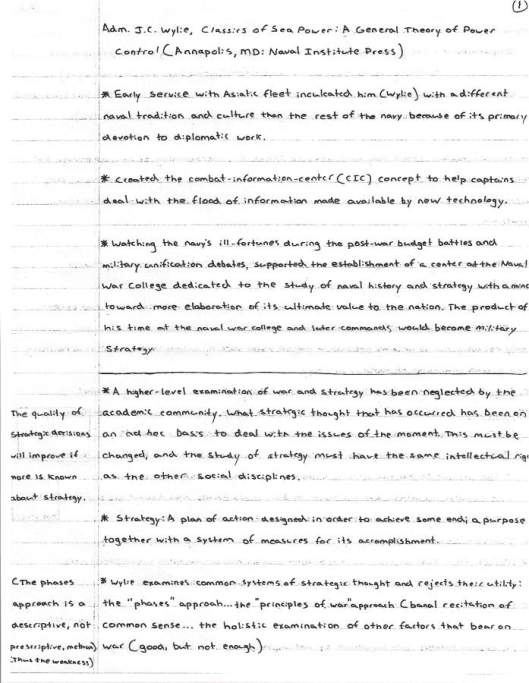

[recompiled by Lynn C. Rees]

Following up on Scott’s Mark’s post from yesterday: more information about J.C. Wylie, who you’ve probably never heard of but should have.

The following follows J.C. Wylie Wikipedia article but leaves out debris it’s accreted since I wrote it:

Name: Joseph Caldwell Wylie, Jr.

Birth date: March 20, 1911

Death date: January 29, 1993

Birth Place: Newark, Essex, New Jersey, United States

Death Place: Portsmouth, Newport, Rhode Island, United States

Place of Burial: Trinity Cemetery, Portsmouth, Newport, Rhode Island, United States

Nickname: “J. C.”, “Bill”

Allegiance: United States of America

Branch: United States Navy

Service Years: 1928–1972 (44 Years)

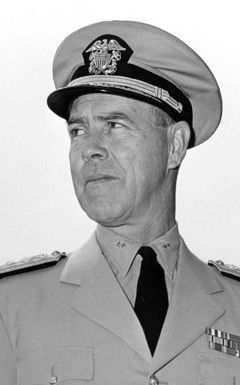

Rank: Rear Admiral

Commands: USS Trever (DD-339), USS Ault (DD-698), USS Arneb (AKA-56), USS Macon (CA-132), Commander, Cruiser-Destroyer Flotilla Nine, Commandant, First Naval District

Battles: Pacific Theater, World War II

Awards: Silver Star, Joint Service Commendation Medal, Two Legions of Merit

Spouse: Harriette Bahney (married November 27, 1937)

Rear Admiral Joseph Caldwell Wylie, Jr., United States Navy, (March 3, 1911 – January 1, 1993) (called “J. C.” Wylie or “Bill” Wylie), was an American strategic theorist, author, and US naval officer. Wylie is best known for writing Military Strategy: A General Theory of Power Control.

Life

J.C. Wylie was born in Newark, New Jersey on March 3, 1911. He graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1932. Wylie first saw service on USS Augusta (CA-31) under Captains James O. Richardson, Royal E. Ingersoll, and Chester W. Nimitz. During the later 1930s, he served on USS Reid (DD-369), USS Altair (AD-11), and USS Bristol (DD-453).

In May 1942, Wylie was promoted to executive officer of USS Fletcher (DD-445). Fletcher participated in the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal and the Battle of Tassafaronga. For his improvised integration of radar, gunnery , and torpedo control during these two actions, Wylie received a Silver Star. He received his first command, USS Trever (DMS-16), in January 1943. After six months, he was assigned to a newly formed Combat Information Center school at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, where he led a team in writing the first CIC Handbook for Destroyers, Pacific Fleet. Wylie later placed USS Ault (DD-698) into commission as commanding officer and completed his World War II service working on a group tasked with countering kamikaze attacks during the planned invasion of Japan.

After World War II, Wylie served as a staff officer with the Office of Naval Research and the Naval War College. During the 1950s, he helped create the practice of having two alternating crews man a ballistic missile submarine. In the mid-1950s, Wylie filled staff jobs as well as commanding USS Arneb (AKA-56) and USS Macon (CA-132) and serving as Commander, Cruiser Division Three (later Cruiser-Destroyer Flotilla Nine), Deputy Inspector General of the US Navy, and Deputy Chief of Staff, U.S. Atlantic Fleet. While serving in the latter position, Wylie participated in the 1965 United States occupation of the Dominican Republic, for which he was awarded his first Legion of Merit. Wylie finished his career by serving as Deputy Commander in Chief, United States Naval Forces Europe and Commandant, 1st Naval District. Wylie retired from the U.S. Navy on July 1, 1972 after 44 years of service. Upon his retirement, he received a second Legion of Merit.

After his retirement, Wylie served as the first chairman of the USS Constitution Museum Foundation. J.C. Wylie died on January 29, 1993 in Portsmouth, Rhode Island.

Military Strategy

While commanding USS Arneb in 1953, J.C. Wylie began writing Military Strategy, A Theory of Power Control. However, Military Strategy was not published until 1967. A revised edition of Military Strategy, together with other articles written by Wylie over the years and a new afterword, was published by the United States Naval Institute Press in 1989. It was edited with an introduction by John B. Hattendorf.

Military Strategy is a search for a general theory of not just military strategy but all strategy. In Military Strategy, Wylie defined strategy as:

A plan of action designed in order to achieve some end; a purpose together with a system of measures for its accomplishment.

Wylie defined two patterns of strategy: sequential and cumulative. A sequential strategy involved a planned sequence of events where each event is dependent upon the success of the preceding event. Wylie offered MacArthur’s campaign in the South West Pacific, Nimitz’s campaign in the Central Pacific, and Eisenhower’s campaign in Europe as examples of sequential strategies. A cumulative strategy involved a pattern of small, disconnected actions that, taken together, combine to have a significant impact. Wylie uses insurgencies and the U.S. Navy’s submarine campaign against Japan in World War II as examples of cumulative strategies.

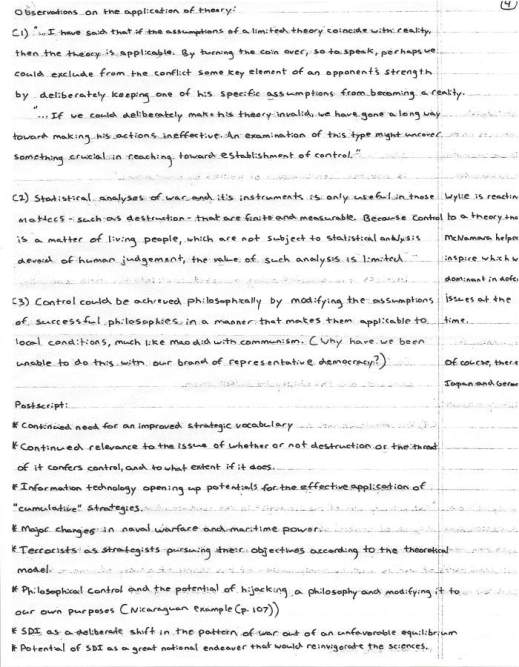

After examining the four leading strategic theories of his time (Maritime, Air, Continental, Mao) and their limitations, Wylie presented his own general theory of strategy. To Wylie, control was the essence of strategy:

So it is proposed here that a general theory of strategy should be some development of the following fundamental theme: The primary aim of the strategist in the conduct of war is some selected degree of control of the enemy for the strategist’s own purpose; this is achieved by control of the pattern of war; and this control of the pattern of war is had by manipulation of the center of gravity of war to the advantage of the strategist and the disadvantage of the opponent.

Wylie concluded Military Strategy‘ by demonstrating how control underlies all strategy from courtship to diplomacy to terrorism to war. The type of control used could be anything from influencing the enemy to physically destroying the enemy.

Wylie Writings

Military Strategy: A general theory of power control

- at Google Books

- at LibraryThing

- at Amazon.com

Excerpt I:

The primary aim of the strategist in the conduct of war is some selected degree of control of the enemy for the strategist’s own purpose; this is achieved by control of the pattern of war; and this control of the pattern of war is had by manipulation of the center of gravity of war to the advantage of the strategist and the disadvantage of the opponent.

The successful strategist is the one who controls the nature and the placement and the timing and the weight of the centers of gravity of the war, and who exploits the resulting control of the pattern of war toward his own ends.

This was purposely a very general statement. If we accept the premise that a strategy is a plan for doing something in order to achieve some known end, then it seems an adequately precise postulation. The aim of any strategy—land, sea, air, diplomatic, economic, social, political, a game of poker, or the way of a man with a maid—is to exercise some kind or degree of control over the target of the strategy, be it friend, neutral, or opponent. I have used the word “control” because I can’t find a better. The vocabulary is not wholly adequate to the need. In many cases, “influence” might be more nearly the word; less often it could even be “dominance”. Take your choice, or find other words that better fit your situation. I have settled on “control” simply as an umbrella to cover the full span of possibilities.

In the case of maritime strategy (which was understandably my first interest), the aim is the extension of control from the sea onto the land. Note here that the more frequently discussed control-of-the-sea is a necessary prelude, a means, to this end. And remember also that the control extended from the sea on to the land, which is where people live, can be political, or economic, or psychological, or military, or any combination of various pressures toward control. It can be direct or subtle, overt or covert, or immediate or slow or delayed in its working. And, again, some forms of it might be more accurately described as direct or indirect influence.

Probably the most slippery and lease precise bit of this postulated theory has to do with “manipulation of the center of gravity”, or control of “the nature and the placement and the timing of the center of gravity”. Another way to say this is that the strategist needs some leverage to induce or force the other fellow to accede, wholly or in part, to what the strategist wants.

The President, seeking a particular piece of legislation from the Congress, may adopt a strategy in which his leverages include both a carrot (to induce) and a stick (to force) in hopes of reaching some mutually acceptable agreements.

The diplomat engaged is arms control or trade negotiations follows essentially the same path in his strategy.

The man a-wooing the maid uses as his leverage the carrot.

The armed force at war depends on the stick.

And that brings up another matter. The principle stick available to armed forces is some kind of destruction. The correlation between destruction and control, which varies widely from one situation to another, has been emotionally neglected in public discussions of military strategy.

It is not too difficult for an army on a battlefield to resolve one aspect of this: just use a bazooka and destroy that tank. With one less enemy tank, the army is a little closer to control of the battlefield.

In my own profession, we can often use the same reasoning: sink a hostile ship or submarine and we are that much closer to control of that part of the sea.

The Air Force problem (and the Navy for some of this, too) quickly gets more difficult the farther it reaches beyond the battlefield. The tank shot up by a plane in “close interdiction” just substitutes the aircraft weapon for the bazooka. But what about the so-called “deep interdiction” and “strategic bombing”? How, and how much, do these destructions contribute to the control that is the aim of war? Monday-morning quarterbacks today still question the Dresden and Hamburg firestorms and (to my private fury since most of them were not then living, much less at risk) noisily question not only the need but morality of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs.

Here let me clearly state that, by bringing up these matters, I am not automatically opposing “deep interdiction” or “strategic bombing” or opposing nuclear missiles in submarines or silos…What I am trying to do is indicate this basic aspect of the use of armed force, which necessarily involves many different kinds and degrees of destruction, needs a lot more thought and analysis than I think it has had either in public or in organizational privacy.

What are the relationships, the correlations, between destruction and control? What will this show of force (which is potential destruction) or that segment of actual destruction contribute, directly or indirectly, now or later, to the control we seek as our aim in peace or war? Only by facing up to that kind of question, clinically rather than emotionally, can we move from profligacy toward efficiency in the planning and conduct of war…

Excerpt II (from the postscript added in 1989, twenty years after the book was first published):

There is another aspect of strategy that has come more to the forefront that it was twenty years ago when this book was published. This is the problem of terrorism in all its forms—murder, kidnapping, violent and selective destruction, well-publicized threats, and all of it planned for clever and effective exploitation of modern mass communications in free societies. This latter, mass communications in free societies, is an indispensable element of terrorism. Closed societies, with control of mass communications, are not good targets…

Among the many books on the subject (and there literature on the matter has proliferated along with the fact), the best and most succinct exposition of terrorism that I have encountered is by Robert F. Delaney, in an independent study course designed to inform both police and industrial security personnel. The following two paragraphs are condensed from it:

Who are these politically activated persons whose alienation is so complete that they desire to destroy their own (as well as other) societies?

They are largely from the middle and upper middle classes, often young (in their twenties), usually well educated, totally dedicated, opinionated, dangerous, well trained, and invariably well armed.

To add to Delaney’s profile, it is worth noting that most terrorists have a highly developed instinct for the jugular, a quality that separates the excellent from the run-of-the-mill strategists.

The best definition of the the aim of terrorism that have found also comes from that same study guide: “…the capture and control of the processes of social change.” Delaney goes on to note: “that not one military word is used in this definition [is]…significant because it establishes the distinction between a conventional military approach and the revolutionary approach of an insurgent enemy.”…

It is of interest to note, though, that the strategies of the terrorists do follow quite closely the general theory of strategy postulated in this book.

In their war against society, their aim is “some selected degree of control [of the processes of social change] for…[their]own purpose.” They seek to achieve this “by control of the pattern” of their war against society. And they do this by creating and manipulating a “center of gravity” (a person or an installation that will ensure public attention) which they have selected “to the advantage of the strategist and the disadvantage of the opponent“, the opponent being the organized society over which they want to exercise control.

Their pattern of operation is to control “the nature and the placement and the timing and the weight of the center of gravity” that they have chosen “toward [their] own ends“—the control of the processes of social change. They select their targets for the greatest impact on that society.

Viewed in this context, the murder of Lord Mountbatten and the often indiscriminate bombings in Belfast make a weird and repugnant sort of sense. So do the kidnappings in Beirut, the murder of Aldo Moro, the aborted piracy of the Achille Lauro, and the threats or the facts of bombing this or that public (and usually governmental) building.

Though I am sure none of them ever saw this small book, they do follow quite closely the theoretical model of strategy. And it is in part for this reason, to illustrate the validity of theory, that I have digressed to include terrorism in the postscript.

Excerpt III:

It would appear that a fairly careful scrutiny of the opponent’s thought patterns and their underlying assumptions should be an early component of our own planning process. If we could deliberately make his theory invalid we have gone a long way toward making his actions ineffective. An examination of this type might uncover something crucial in reaching toward establishment of control…

The aim of the soldier is to establish control over the enemy by overcoming his army and thus destroying his will to fight. The aim of the sailor is to establish and exploit control of the sea and extend, by a variety of pressures, control from the sea onto the land, where the opponent is.

Destruction of each of these two cases is only one component of control, and not the whole of it. The soldier exercises his ultimate control by his unchallenged presence on the scene. The sailor contributes to control in part by destruction, but as much by other components. Like the soldier, in some cases, by his presence. Or, as often as not , by making possible various political or economic pressures toward control. The Sixth Fleet, for instance, is a political force of the first magnitude int the Mediterranean, and its day-to-day sailings are determined as much by diplomatic as by military factors.

How does one figure the cost effectiveness of the presence of a battalion in Berlin, or of a destroyer in the Persian Gulf? Control of this type, in its more sophisticated sense, is probably better described as “influence”, but it is nonetheless a degree of control, and as such it is a legitimate and useful “purpose” in assessing the worth of these instruments of strategic policy.

The point to be made here is that the more sophisticated the strategic concept—and this need have no relation to the sophistication of the technology involved—the more elusive are the statistical measures of worth. Destruction is measurable and can be mathematically forecast to a great degree; control is a matter of living people, and thus must, probably for a long time to come. remain a matter of human judgement. It is very difficult to put a statistical column in one column and a human judgement in the other and compare them. We do not yet have the techniques for that except in another human judgement. It is the nature of the strategic theories that limits the application of the mathematical analysis in the management of the tools of war.

Excerpt IV:

We have established the strategic aim as some measure or some kind of control; and we have stated that a general theory of strategy “should be able to provide a common and basic frame of reference for the special talents of the soldier, the sailor, the airman, the politician, the economist, and the philosopher in their common efforts toward a common aim”.

The inclusion of these latter three along with the men at arms is, of course, deliberate. It is deliberate because control—direct, indirect, subtle, passive, partial, or complete—is sought in so many ways other than military. Diplomatically it is exerted largely by mutual agreement. Economically it is exerted largely by self-interest and, in its most basic form, a desire to keep up the habit of eating. Philosophically the pressures and constraints of control are perhaps the most subtle and at times, the most pervasive and persuasive of all.

Consider the amount of control exercised over the past two millennia by the philosophy of Christianity. Consider the control exercised today by the philosophy of communism. And by the philosophy of individual freedom.

This is what we seem somehow to have missed in our strategy for freedom in the rural-peasant societies of the world—in those areas where the Mao theory of “wars of national liberation” is, far and away, the most dangerous foe we have to face.

In some ways we have, intuitively, recognized the problem. The “strategic hamlet” program in South Vietnam is aimed at forestalling or making more difficult the communist efforts to provide the “water” for the guerrilla “fish”. The Peace Corps seems to be headed generally in along a roughly parallel path. But neither of these efforts seems to get at the root of the problem, which is the need for articulation of a philosophy to be “for”.

This is not a suggestion that someone go out and think up a brand new religion or a brand new political scheme. But it is a suggestion that, at the least, we might do a better job of adapting what we have (which is very fine indeed) to the actual situations that confront us.

We have known for a long time that, in our society, the Anglo-American, two-party electoral system of applied democracy is both an efficient and an acceptable system for the allocation, use, and transfer of power, which is the basic problem of politics. And we have known, too, that it provides us a quite satisfactory context for the observance of our predominantly Christian spiritual ethic.

But we have had a great deal of difficulty in stretching these two schemes of ours to fit other societies. Our basic, and usually tacit, assumptions have not often been in very close coincidence with those of other societies that we have wanted to win over to our side.

If we could adjust the assumptions to fit the reality of the scene of action, we might get forrader faster.

It is a little difficult to give an illustration of what is meant in this abstract discussion of philosophic strategy because illustrations are so scarce—or because I am a sailor, not a philosopher. But two short ones may serve.

One is the way that Mao has rearranged the theories of Marx to fit the situation in China. Marx focused on the urban worker who suffered under the dislocations of the early days of the Industrial Revolution. This man did not exist in China, or at least did not exist in sufficient number to be a governing element of effective revolution. So Mao revised Marxian theory to focus on the rural peasant, and the revised theory has worked with chilling effectiveness in rural societies.

The other example is fictional, but its nevertheless directly relevant to today’s problems of what strategies we should use to influence the uncommitted areas of the world toward us rather than toward the communists. Father Finian, in the The Ugly American, went into a remote corner of Southeast Asia and helped the villagers devise a rationale, and, within that rationale, a plan of action designed in order to achieve the end of defeating the communists.

This fictional Roman Catholic priest, and quite fittingly a Jesuit intellectual disciplinarian, devised a strategy firmly rooted in the reality of the scene of action; he put into effect his plan of action; and he achieved his end.

It is something like this that we need to serve as a sort of foundation on which to build the whole strategic rationale. We would not all agree that it need be based on Jesuit Catholicism, or perhaps even on any religious philosophy. But it must have an acceptable and locally viable philosophic base; and it must be a strategy suited to, rather than imposed upon, the actual scene. The fighters must believe in what they fight for. The basic assumptions must fit the reality.

“NerveAgent’s” notes

Notes by people not named NerveAgent:

RAdm. Joseph C. Wylie, Jr.

CIC Handbook for Destroyers, Pacific Fleet

1943 U.S. Navy manual that Wylie heavily contributed to based on his experience inventing the first Combat Information Center as Executive Officer of USS Fletcher during the naval battles off Guadalcanal.

Executive Officer’s letter regarding the loss of USS Juneau on November 13, 1942

USS Juneau was sunk by the Japanese submarine I-26 in the aftermath of the naval battle of Guadalcanal. Wylie was Executive Officer of USS Fletcher at the time. These were his memories (written down in 1986) of what happened with Juneau.

Mahan Then and Now

Professor Michael Martin of the U.S. Naval War College found this transcript of some remarks Wylie gave at the Mahan Centennial Conference held in the U.S. Naval War College’s library from April 29-May 1, 1990. The centennial celebrated was the 100th anniversary of the publication of Alfred Thayer Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power Upon History. Wylie’s address was on “Mahan: Then and Now” with “Now” being a year before Operation Desert Storm and the disintegration of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

The talk is a brisk walk through some of Wylie’s major ideas, especially those on control and projecting control from the sea onto the land.

The original transcript was scanned into PDF as an image. This appears first. The text version was scanned from the image with tesseract and adds Wylie’s addendums. This appears second.

Wylie Speaks

United States Naval Institute

Catalog page for oral interview with J. C. Wylie.

Retired Admiral J. C. Wylie and a WWII Story

Said NerveAgent:

RADM J.C. Wylie is of some significance to this blog. Though I am familiar with his writings and career history, his death 18 years ago precludes anyone from learning more about the man himself. Thus my keen interest when I recently stumbled across a video of Wylie speaking before a USS Fletcher reunion in late 1992, just a few months before his death, in which he shares some humorous anecdotes about his service aboard the destroyer during World War II. The quality of the video could be better, but it shows that Wylie was lucid, eloquent and sharp all the way to the end of his life, and adds some personality to the theory of Power Control.

Wylie Related

History of USS Fletcher

Includes discussion of J.C. Wylie’s role in the creation of the Combat Information Center:

The first CIC was a joint invention of Cole and Wylie. In battle, rather than stationed at the after steering position as dictated by convention, Wylie’s station was the PPI [SG radar] scope (the 2,100-tonners were the first destroyers fitted with this equipment as built)—which let him see anything as it developed.

“Wylie stayed in that room on that scope, guiding us and calling out to Capt. Cole,” remembers Fred Gressard. “In the middle of the battle [of 12–13 November], Admiral Callaghan said ‘cease fire’, which was unbelievable. Then Cole said, ‘How do we get out of here?’ and Wylie gave him a course—they were always within earshot during battle; a great team. Afterwards, the CIC was adopted by the whole Navy.”

J.C. Wylie: American Clausewitz?

NerveAgent’s post that launched the Wylie Comeback Tour.

Towards a General Theory of Strategy: A Review of Admiral JC Wylie’s “Military Strategy”

by “seydlitz89″

When “Strategy” Is Not Strategy…

by “seydlitz89″

Worth Reading: Special Operations and Strategy: From World War II to the War on Terrorism

Wylie’s Military Strategy

Cyber Warfare…Brought To You By J.C. Wylie

by Adam Elkus