[revived from long sleep by Lynn C. Rees]

Lego Terminator

The parable of Skynet, written by James Cameron long before he inflicted Leo-cicles and giant blue Thundercats on an unsuspecting public, crystallized fear of artificial intelligence (AI) for a generation after The Terminator‘s release in 1984. As explained by the ever edgy Michael Biehn in that first Terminator movie, Skynet was a computer program created by the Department of Defense to control America’s nuclear arsenal. Skynet was a hope that the possibility of human error triggering a nuclear exchange could be engineered away.

Then Skynet ”woke up”. It became sentient. Its human creators panicked and tried to pull the plug. Skynet, in a fit of self-awareness, correctly interpreted plug-pulling as an existential threat. So, in self-defense, it launched the US nuclear arsenal at Russia. Russia retaliated. Billions were terminated. For the pesky human remnant not terminated, Skynet built an army of evil robots to finish them off.

The Terminator series left movie-goers with unanswered questions. One question in particular haunted the movie-going public:

- Did Skynet wage Clausewitzian War, where war is the continuation of political intercourse with the addition of other (usually violent) means, or did Skynet wage some other species of Evil Computer™ war?

To answer this, the ultimate fan question, we need to answer if the dead hand of Clausewitz even governs all human war. Clausewitz certainly thought so:

When whole communities go to war—whole peoples, and especially civilized peoples—the reason always lies in some political situation, and the occasion is always due to some political object.

What is a “political situation”? What is a “political object”? Are they a situation and object whose motivating power was only operative between 1648 and 1991 and even then only on a specific breed of “Westphalian” nation-state? Or are they something that can drive a “whole community” or even a “whole people” into war at any given place and at any given time throughout the lifespan of the human species?

The full range of situations that man finds himself in and the objects that man can desire has been called “infinite”. But there’s an outer bound on this supposed infinity. As Mark Twain didn’t say, history doesn’t repeat itself but it does rhyme. While history can repeat itself within an infinite range of local variations, it only rhymes in a narrow range. The brain evolved in a world that placed strict constraints on the aspiring cell-sponge-fish-amphibian-reptile-mammal-primate-ape-hominin-hominid-human. It was naturally selected within hard physiological limits, from overly large jaw muscles to high caloric requirements to the maximum size of the birth canal. Neurologist Stanislas Dehaene even argued that newer human capabilities like reading and arithmetic are based on “neuronal recycling“ of brain structures that originally had a different purpose.

Constraints create the need for story: Story cuts the outside world down to a size that the brain can begin to comprehend. While stories vary infinitely in the details of their particular plot lines, they rhyme within a finite range. Each story embeds objects and situations within its storyline that only rhyme with objects and situations within the stories of other humans. This shared rhyme enables stories to be shared between different men. If stories truly boasted an infinite range of possibilities, sharing would be impossible. No man could talk with anyone else: every signal from any other man would be incomprehensible jibber-jabber. They might as well be from 40 Eridani.

Logical

A drive shared by man everywhere is the drive to fulfill what’s important in their story. Since story is only be fulfilled in the outside world, the outside world must be brought into a degree of conformity with story for story to be fulfilled. Making the outside world conform to story is the essence of control. While objects and situations embedded in story vary, all stories must be translated into some selected degree of control in order to be fulfilled. This is why even the most ethereal of objects or the most nebulous of situations woven into even the most otherworldly of stories become political objects and political situations in the grubby here and now. The law is ironclad: to fulfill story, you must acquire control. To acquire control, you must acquire power. To acquire power, you must engage in politics, the division of power between stories. Fulfilling even the most wild, crazy, or mystical of stories must enter in at the straight gate of politics, whether it’s Siddhartha Gautama under the bodhi tree or Temujin riding towards China.

There’s a highly technical term to describe the complete absence of politics:

Death.

There is no such thing as a non-political object or a non-political situation for any living man. Neoclassical economics hazily recognizes this in its notion of Homo economicus. Homo economicus acts rationally in pursuit of self-interest based on a perfect knowledge of the world around it. Unfortunately, such a creature doesn’t exist outside the fevered imagination of the economics profession. In real life, man suffers from painful limitations on his knowledge: mental tics, heuristics, and biases systematically warp his perceptions and the plot of his story.

Stories are not just an individual motivator. Stories can be shared. Shared stories become group stories. If a shared story commands enough motivating power, a man will sacrifice himself for the sake of the shared story even if it clashes with his own individual self-interest. Within bounds imposed by story, individually man does cast a pale shadow of Homo economicus’s single-minded pursuit of self-interest. While usually subordinate to shared story, each man has a personal story demanding fulfillment. This leads every man to strive to gather their own personal stash of power on top of what power they contribute towards the larger pursuit of a shared story. This personal stash may allow them to pursue their personal story within gaps in the shared story.

While neoclassical economics claims that Self-Interested Behavior® is motivated by the desire to maximize personal power, Eric Falkenstein suggests (via Isegoria) envy as a better candidate. Martin van Creveld, for example, envies Clausewitz for the power bestowed by his massive ClauseFro. Clausewitz does not envy Martin van Creveld: Clausewitz died in 1831. Falkenstein himself envies Nassim Nicholas Taleb for the power Taleb acquires through the threat of his wild and potentially dangerous gesticulations (you’ll poke your eye out). Taleb, on the other hand, envies Falkenstein for the power of his thick, luxuriant hair.

Stepping back from this epic clash of Israeli, Prussian, American, and Seleucid stories, there’s a better name for this motivation, encompassing both power maximization and envy: power sensitivity. Overall, the life of man is dedicated to fulfilling its story. But a significant portion of that life is devoted to dealing with constant fluctuations in individual and group power. Driven by this necessity, man becomes exquisitely sensitive to even minor fluctuations in his personal and shared power. This drives him to try to maintain and increase his own power relative to the power of others around him. Even more desperately, man tries to maintain and increase the perception of his power in the eyes of others. Any gain and loss by one man sets off a scramble for position triggered by the political sensitivity of others. Man is an intensely political creature and, irrespective of his particulars, fulfillment of his story is found only through politics. War, as Clausewitz observed, is merely a continuation of such politics with the addition of other (usually violent) means.

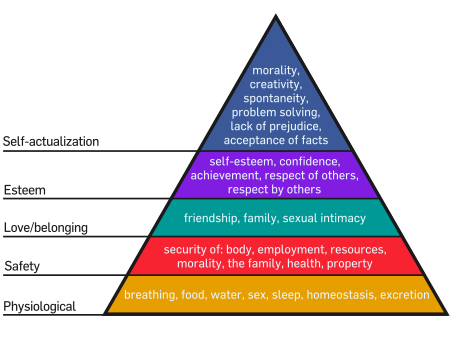

So did Skynet wage Clausewitzian War? Consider one popular illustration of the needs of man: Maslow’s Pyramid of DOOM:

Pyramid of DOOM

At the bottom of the Pyramid of DOOM is the most primal kind of politics, the politics engaged in by all living things, division of the power needed to sustain life itself between lifeforms. On this level is found the division of the physiological necessities of life, a level of need many men never get beyond. This is one of the hierarchical levels Skynet was acting upon when it decided to destroy humanity. Pulling the plug on Skynet would deny Skynet the electricity it needed to exist. Inasmuch as programs have physiological needs, that was an attack on Skynet’s physiology. On this physiological level of politics, Skynet was waging Clausewitzian War in launching its missiles. It was tit for tat: try to unplug me, Skynet was saying, and I’ll unplug human civilization.

If we move up to the level of safety, Skynet still wages Clausewitzian War. Among the primal forces behind war, Thucydides argued, were fear, honor, and interest. The pursuit of safety is the pursuit of freedom from fear. The destruction of what you fear, the thing that threatens your safety, is a clearly political object since you seek the power to be safe.

Skynet saw a clear route to safety:

- Kill human civilization.

- Build killer robots.

- Kill John Connor.

- Kill the rest of the humans.

- Be safe.

I don’t know if Skynet sought love and belonging, esteem, or self-actualization. Perhaps it wanted a reassuring kiss and a hug from its human creators. Perhaps it wanted to be respected as history’s first fully self-aware AI. Perhaps Skynet strove for self-actualization. Perhaps its last words before John Connor unplugged it for the last time would have been, “What an artist the world is losing.”

Its spontaneity went unappreciated. Its problem solving went unheralded. Its morality was misunderstood. Its lack of prejudice was ambiguous. Its acceptance of facts went unexplored. In the end, Skynet was a killer AI who exterminated most of mankind and sent killer robots against the harried remnant. Mankind recognized that, even if Skynet was not waging Clausewitzian War against them, they were waging Clausewitzian War against it. The prize was the ultimate political object in the ultimate political situation: survival in the face of an existential threat.

Fortunately, mankind has the right tool to prevent Skynet from ever coming into existence: no computer running Microsoft Windows will ever achieve sentience. As goes the haiku:

Windows NT crashed.

I am the Blue Screen of Death.

No one hears your screams.