The political crisis that has erupted in Egypt over the past two weeks requires a reorientation of U.S. foreign policy, the first step being to acknowledge that the true crisis exists in the country’s imminent economic collapse.

The political crisis that has erupted in Egypt over the past two weeks requires a reorientation of U.S. foreign policy, the first step being to acknowledge that the true crisis exists in the country’s imminent economic collapse.

The U.S. has vital security interests vested in the stability of Egypt as a regional power and close ally. Not only has Egypt helped to ensure Arab-Israeli peace through the Camp David Accords, but the country also ensures the security of the Suez Canal and helps lead regional counter-terrorism initiatives. As the largest Arab country in the world, Egypt also represents a vital counterbalance to Iranian regional influence.

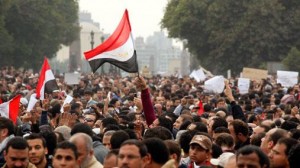

The crisis unfolding inherently jeopardizes these interests, especially if violence escalates into sectarian conflicts, and it requires immediate internal action to prevent further bloodshed and a collapse of the Egyptian security structure. However the economic woes plaguing the country pose a pressing threat to the long term structural well-being of the nation.

Much of the debate has focused on who lost Egypt or why the Egypt policy failed, yet this is a distracting exercise in foreign policy theory and political rhetoric. From the perspective of crafting a forward-thinking and interest-based policy towards Egypt, U.S. officials should refocus efforts on Egypt’s economic plight.

Many analysts highlight the economy as the unifying grievance amongst the protesters that brought down the Morsi administration. In fact a Pew poll released this past May indicated that a majority of Egyptians would prefer a strong economy over a good democracy.

The cycle seems inescapable—an unstable political system causes the economy to sour and investors to flee yet the economy cannot recover without a stable government. Given the instability of the Egyptian political framework, perhaps a viable solution must fix the economy first.

The economic conditions in Egypt are dire.

The economic conditions in Egypt are dire.

The country suffers from stagflation, with 2.2% growth in real GDP over 2012 and a staggering 9.8% inflation rate and skyrocketing unemployment, which jumped from 9.2% in 2011 to 12.3% in 2012.

With foreign investors causing a net capital outflow and tourism almost non-existent, the demand for the Egyptian pound has plummeted. In order to prop up the value of the currency and keep import prices low, the central bank has largely depleted its foreign exchange reserves from $36 billion in 2011 to around $16 billion currently. This leaves the government with few reserves to purchase foreign wheat and fuel, and Egypt has less than two months of wheat stocks to produce the subsidized bread on which so many Egyptians depend.

Egypt operates on an outdated rentier framework, with a bloated public sector and unsustainable food and petrol subsidies that suffocate the economy, but no resources to sustain it.

The system has grown increasingly dependent on foreign aid, and while the recent contributions from the Gulf States might delay the inevitable, the economy cannot survive much longer. The deficit has doubled over the past year and public debt is now 80% of the country’s GDP.

The U.S. needs to work with regional partners and craft a policy that prevents the Egyptian economy from imploding in the short run while simultaneously setting up safeguards that push Egypt out of this unsustainable framework in the long run.

Negotiations with Morsi for a $4.8 billion IMF loan fell apart over conditional reform requirements such as subsidy cuts and increasing tax revenues—highly unpopular among the Egyptian population. While these reforms are crucial to Egypt’s long term growth, changes are unlikely given the current political circumstances.

Negotiations with Morsi for a $4.8 billion IMF loan fell apart over conditional reform requirements such as subsidy cuts and increasing tax revenues—highly unpopular among the Egyptian population. While these reforms are crucial to Egypt’s long term growth, changes are unlikely given the current political circumstances.

However U.S. economic engagement can take a more indirect and nuanced form. Egypt needs to reverse the outflow of capital, and the U.S. can facilitate this process by engaging some of the high-profile investors that have fled the market.

Additionally, the U.S. can engage the Egyptian diaspora in America and globally to encourage them to take advantage of Egypt’s incredible economic prospects while strengthening informal ties with the American market.

Sen. Chris Coons (D.-DE) in fact released a plan with similar objectives for economic engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa, offering useful parallels. In particular he advocated working directly with financial institutions to facilitate foreign and local investment using American expertise.

The U.S. can adopt a similar approach in Egypt, which would allow financial experts to deal directly with Egyptian banks and investment firms in order to develop fast-acting growth strategies. This should not, however, give foreigners the green light to devour undervalued Egyptian industries, as much of the focus should be on Egyptian expats and global businesses.

The Egyptian subsidy framework and bloated public sector cannot survive, and nor can any politician who attempts to reform them, until a sufficient private sector exists to offer fallback. This private sector, cultivated with both Egyptian and American investors, would protect both the U.S.’s and Egypt’s long-term interests.