Initial positive indications from officials regarding emergency management during Hurricane Sandy suggest that national resilience to unforeseen events has vastly improved, especially since 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, two formative events in the homeland security discourse. Whether this improvement is due to formal federal reconfiguration, informal acknowledgment of the need to respond swiftly, strong executive leadership, or (likely) a combination of the aforementioned, Sandy likely cements the recognition of natural disaster response as a part of our collective domestic security.

Initial positive indications from officials regarding emergency management during Hurricane Sandy suggest that national resilience to unforeseen events has vastly improved, especially since 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, two formative events in the homeland security discourse. Whether this improvement is due to formal federal reconfiguration, informal acknowledgment of the need to respond swiftly, strong executive leadership, or (likely) a combination of the aforementioned, Sandy likely cements the recognition of natural disaster response as a part of our collective domestic security.

As clean-up from Hurricane Sandy continues and the rebuilding process begins, our national response to the historic storm should be examined through the lens of governmental organization. Though many of the ground-level emergency personnel from FEMA, DoD, and state/local agencies would likely have made it to the scene in some capacity as part of a natural disaster response fifteen years ago, the coordinating mechanism has been jiggered considerably. This is a result of a targeted effort to expand our collective concept of homeland security to include personal security as discussed in American Security Project’s recently released Climate Security Report.

Expanding homeland security to all elements of safety provision beyond the traditional Westphalian state model described yesterday by ASP board member Lt. General Daniel Christman includes building national capacity to respond to a plethora of natural, technological, and economic threats in addition to defense from non-state actors. Whereas the defense and intelligence communities are largely tasked with preventative action against state and non-state aggressors, DHS’s range of duties includes both preventative and responsive action.

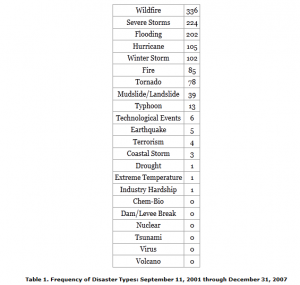

The evolution of homeland security to its current inclusive state has been a somewhat rocky process. Christopher Bellavita observes that simply establishing a cabinet-level department of that name hardly etched out a well-defined identity, especially among so many previously separate agencies. While the department’s early mission was more focused on the prevention of terrorism, the all-hazards definition of homeland security as presently en vogue began to take root later, around 2007. Even then, the all-hazards approach was not explicitly broadcast to the public by DHS. However, as the frequency of natural disasters – and the resulting need for emergency responses by governmental agencies – outpaced domestic terrorism at an exponential rate, the shift toward all-hazard response was solidified. Conveniently, the same infrastructure and process that exists to respond to a natural disaster could also be employed in the event of a far less probable terrorist or state attack upon the US homeland.

Christopher Bellavita, “Changing Homeland Security: What is Homeland Security?.” Homeland Security Affairs 4, issue 2 (June 2008)

The response to Sandy demonstrates an effective transformation allowing FEMA to serve as the figurative head of the unified effort while DoD (including National Guard), Coast Guard, and state/local emergency responders and law enforcement serve as the functioning body parts. The enhanced coordination is likely a result of the institutionalization of DHS’s administrative function solidified after ten years of existence. The logistical and personnel capacity lacked by DHS is more than made up for by the supporting agencies and their willingness to take orders during an emergency response. Certainly at the state and local levels, responders hardly sit on their hands waiting for orders from FEMA, but the federal support function missing in New Orleans following Katrina is no longer cited as a shortcoming as we react to Sandy.

As the causal link between climate change and natural disaster frequency/intensity becomes more evident, Hurricane Sandy places a bulls-eye on that relationship. Scientific research alone may be insufficient to cause policy change, but public opinion acknowledging the effects of climate change should drive lawmakers’ accountability to ensure preparedness and enable agencies to mitigate the effects of natural disasters. As that process progresses, DHS (FEMA in particular) appears to have found solid footing in disaster planning and response as an accepted aspect of homeland security. The longstanding debate over whether FEMA – and its response mission – belongs in DHS becomes a moot point if an inclusive concept of homeland security is embraced through government agencies and the public, beyond the department. Sustained leadership and outreach should aim to widen the American definition of national security to the holistic range of challenges spanning from the environment to economics.