[ by Charles Cameron — remembering my father, Capt Orford Gordon Cameron, DSC, RN ]

.

I came across two pieces with overlapping descriptions of what happens to the body, perceptions, and thought, in a firefight. As is my habit, I’ve picked some of the essential text and accompanying illustration in each case, and offer them to you in my DoubleQuote format:

**

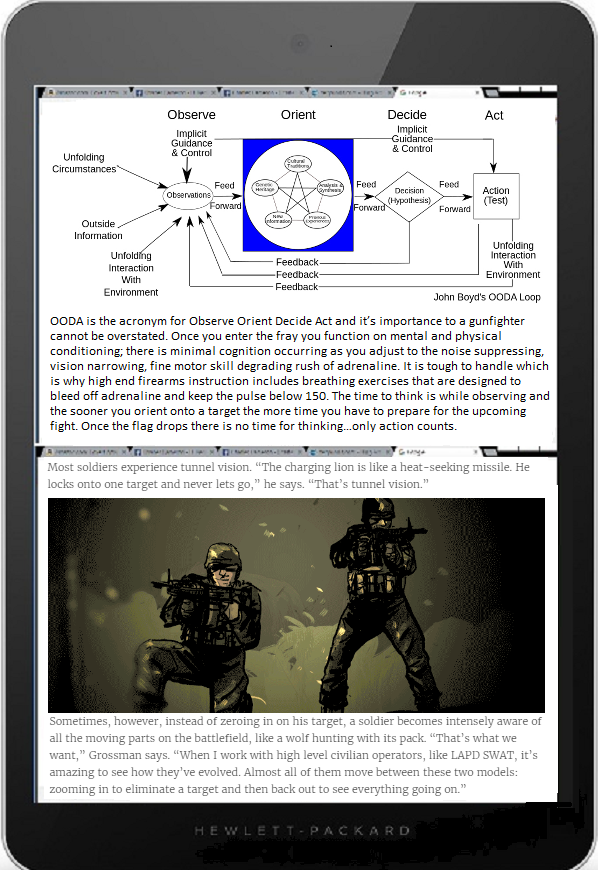

The first quote, with the Boyd OODA Loop diagram heading it, comes from Tim Lynch‘s Fourth Generation War Comes To America: What Are You Going To Do About It?, which Michael Yon linked to.

Lynch’s piece is his response to the Orlando shooting, its thrust being that the event went on way too long, and that we need more people to identify (and prepare) themselves as sheepdogs:

Human Sheepdogs are, by nature, not a threat to their fellow citizens but are death dealing fighting machines when they, their loved ones or the sheep (other citizens) are in peril.

In particular, Lynch delivers a mini-seminar on the essential contents of two books:

LTC Dave Grossman, On Killing Gavin de Becker, The Gift of Fear

The second comes from Adam Linehan‘s This Is Your Brain On War at Task & Purpose. Again, the topic centers around Grossman’s work, but in this case the framing has to do with the tranfer of psychological insight from sports medicine to the military profession.

There’s more in Linehan’s piece that’s relevant to my posting here than I’ve been able to quote in my “tablet” DQ format, so here’s some additional detail:

The moment an engagement kicks off, the body initiates a dramatic response, beginning with the circulatory system, which immediately shunts blood away from the body surface. This, Grossman explains, is the body preparing to suck up damage.

Preparing to absorb damage, the circulatory system moves blood away from the body’s surface to its core.

“It’s called vasoconstriction. Just before the capillaries, there’s a mechanical shutdown of the blood flow, and now the arteries and the body core are holding up to twice as much blood. That’s why the face goes white.”

There are two primary reasons for this. One, it helps prevent bruising, which is what happens when the capillaries and veins burst from blunt force trauma. If there’s no blood, they remain intact. But more importantly, the redirected blood flow helps keep the person alive long enough to finish the fight. [ .. ]

Blood drains from the brain’s rational control center (the forebrain), leaving the midbrain in full control, at which point, you will do what you’ve been trained to do.

That’s because, at its most extreme, vasoconstriction affects the brain, too. “As the blood drains from the face, blood drains from the forebrain, and there’s no rational thought,” Grossman explains. “I call that ‘condition black.’ And at condition black, the midbrain is in charge, and you’ll do what you’ve been trained to do — no more, no less. You will do what you’ve been programmed to do — no more, no less.”

Thus, if a soldier reaches condition black and lacks adequate training, there’s a good chance he or she will freeze up. A well-trained soldier, on the other hand, will likely take action to neutralize the threat. “Given a clear and present danger, with today’s training almost everyone will shoot,” Grossman says.

There are specific impacts on perception, too:

Many soldiers report barely being able to hear the blast of their own rifles during combat.

“The lion’s roar is a deafening, stunning event,” says Grossman. “But the lion doesn’t hear his roar, just like the dog doesn’t hear his bark. Their ears shut down, and so do ours. Gunpowder is our roar.”

Under high stress, the nerve connecting the inner ear and the brain shuts down, resulting in temporary hearing loss, or “auditory exclusion.”

This phenomenon is called “auditory exclusion,” and it’s a result of the nerve that connects the inner ear and the brain shutting down in the heat of battle. According to Grossman, 90% of combat soldiers report having experienced auditory exclusion. “You get caught by surprise in an ambush. Boom. Boom. Boom. The shots are loud and overwhelming. You return fire, boom. The shots get quiet, but you’re still getting hearing damage.”

A soldier’s vision can also be affected by combat, and Grossman uses two different so-called predator models — the “charging lion” and the “wolf-pack dynamic” — to explain this.

This is where the quote I selected about two types of vision — one in tight focus, one diffusely aware of everything going on around you — kicks in.

And one more thing: there’s time-dilation.

A number of soldiers and law enforcement officers whom Grossman has interviewed reported being able track incoming rounds with their eyes.

There is another phenomenon involving vision that is widely disputed, but which Grossman insists is real, and that’s the experience of what he calls “slow-motion time.”

“I have had hundreds of people tell me they can see the bullet in combat,” he says. “Many have been able to later point to where the bullet hit, and they could not have done that without tracking the bullet with their eyes. Not like the matrix. It’s like a paintball, where the bullet is slow enough you can track it with your eyes.”

**

I’m not much of a gun person — though this is Father’s Day, and I do recall going on exercises aboard my father‘s command (Royal Navy) when I was nine, and firing the Oerlikon and Bofors guns. Why, then, am I interested enough in these two articles to recap them together here?

It’s because I’m a meditator, and concerned with breath and matters of cognition — so “high end firearms instruction includes breathing exercises that are designed to bleed off adrenaline and keep the pulse below 150” speaks to my daily practice — not because I’m in firefights, but because I want to enter a state of peace, and remain peaceable even when not meditating.

And that, my friends, means there’s some common ground between warfare and peacefare right here, in the breath. Which is something I think should be of keen interest to all of us.

Linehan’s article goes into more detail regarding cognition under fire, but two points particularly strike me. The first is that he mentions two states, often in rapid alternation, one involving tightly focused awareness, and the other a wide-angled awareness of 360 degrees around you, not to mention above and below..

That interests me because there are two major strands of meditative practice, one using a tight focus (eg on the breath, a mantra, etc), and the other picking up on whatever crosses the threshold of consciousness, not only from all around your external environment, but also from the various streams of bodily sensations, emotions, and thoughts. Mantra meditation is of one kind, zen sitting an example of the other.

Don’t take my word for it, though, I’m probably missing some important subtleties, and practice under the watchful eye of a teacher will give you a far better sense of the distinction and its niceties than I can.

The last thing? Time dilation.

It’s my experience — sometimes in meditation, but perhaps most noticeably when I was in a car rolling over and over in the Nevada desert — that time as perceived can both slow down and speed up. There can be all the time in the world to notice every last detail of what’s happening — and it can all be over in a flash, a split-second.

Words really don’t do such experiences justice, so I’ll leave it at that. But the similarities and commonalities between military experience under fire and meditative experience in the cool of the day are striking enough to warrant in-depth study — or as the meditation community might out it, further contemplation.