[ by Charles and Emlyn Cameron — my thousandth ZP post, and his first — in which my son schools me in making my games more responsive to the requirements of decision-support ]

.

**

I’d been wondering what to do with my thousandth post here on Zenpundit, and a conversation with my son Emlyn, who turned nineteen a few days ago, gave me an idea.

Emlyn was telling me how he saw my HipBone Games, and also the more extended and informal version of the games I’ve been posting here — using “HipBone thinking” to analyse and comment on all manner of things happening in the world around us, with a particular eye on a novel, mental-netted mode of intelligence analysis. He spoke, I was impressed, and asked him to write his observations up, to form the basis of this, my 1,000th ZP post.

Here he goes:

I consider all my father’s thoughts to be rather like a mobile, which in turn I consider to be the three-dimensional equivalent of a HipBone board: many swirling clusters of information, spinning, for the most part, independently of one another, balanced, but lacking a focus. They are connected, but some are so only by virtue of their association with a shared cluster between them. These clusters are creative and constructive, but typically inconclusive in their determination of any particular fact to which they all play a part. Father has made some comments to this effect, claiming that the games might widen the perception of intelligence analysts, making them more fully aware of political situations in which they involve themselves, but admitting that it might not be a mechanism for reaching conclusions about the next step to take in said situations…

That’s fierce enough, and very much to the point. I’m generally more interested in open questions than closed answers — and in my post, Wei Wu Wei, or the inactionable option, I wrote of “the importance of intelligence that is not actionable, with illustrations from Zenpundit, Dickens and Shakespeare” — and closed with a gobbet of my favorite Chinese philosopher, Chuang Tzu.

But then Emlyn, having understood me all too well, opens an alternative pathway…

it is my conviction that such a use [ie in “reaching conclusions about the next step to take”] is only missed by the barest margins in the construction of the games, that, in fact, a figure has been presenting the use of such a thought process towards such ends since the eighteen-eighties: Mycroft Holmes.

I’m delighted, too, that Emlyn finds something about my work that resonates with his own keen interest in the Holmes brothers, favorites of his both in their canonical Conan Doyle and more recent Benedict Cumberbatch forms.

As for the Calder mobile effect — ideas hanging in some kind of perpetually shifting balance in three-space — I’m reminded of the pebbled path which leads through shrubs and bushes and cactus plants around Pierre Sogol‘s attic studio in René Daumal‘s great novel, Mount Analogue:

Along the path, glued to the windowpanes or hung on the bushes or dangling from the ceiling, so that all free space was put to maximum use, hundreds of little placards were displayed. Each one carried a drawing, a photograph, or an inscription, and the whole constituted a veritable encyclopedia of what we call ‘human knowledge.’ A diagram of a plant cell, Mendeleieff’s periodic table of the elements, a key to Chinese writing, a cross-section of the human heart, Lorentz’s transformation formulae, each planet and its characteristics, fossil remains of the horse species in series, Mayan hieroglyphics, economic and demographic statistics, musical phrases, samples of the principal plant and animal families, crystal specimens, the ground plan of the Great Pyramid, brain diagrams, logistic equations, phonetic charts of the sounds employed in all languages, maps, genealogies — everything in short which would fill the brain of a twentieth-century Pico della Mirandola…

**

Emlyn again, when I requested he go into a little more detail:

In regards to the difference between my father’s manner of thinking and that of, say, a Holmesian detective, the largest separation presents itself, not in the construction of a conceptual geometry for the facts, but in the selection of a focal point. That is to say the Holmesian analyst has one.

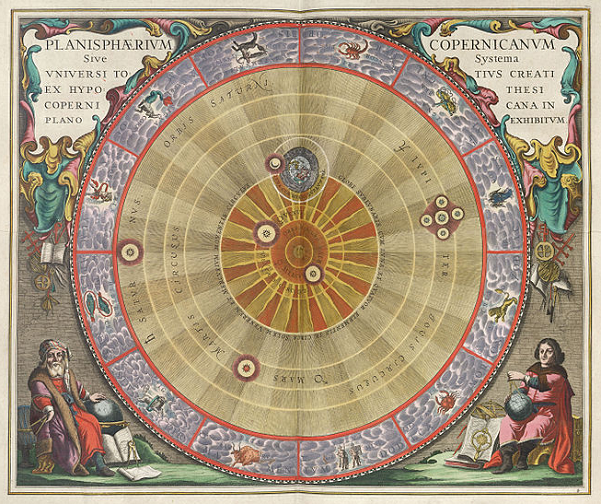

Where my father’s constructions are clusters of concepts hanging in their own orbits, connected with fibers between one element of one cluster and one element of another, the Holmesian mindset is clusters of facts arrayed around a single unknown, like the spheres of a model of the Copernican solar system (ironic, considering Sherlock’s reluctance to retain such a universal model in his memory palace), each piece of data added to the strata of information bringing the silhouette of the solution into greater clarity, until finally, only one plausible answer can be found to match the shape.

Mycroft makes himself the “most indispensable man in the country” simply by centering a single point for all of his data, connecting each strand of thought to an innermost axis, the unknown he wishes to conquer, invariably finding an effective solution even to difficulties involving “the Navy, India, Canada and the bimetallic question… Only Mycroft can focus them all, and say offhand how each factor would affect the other”.

Father, on the other hand, foresees largely important cultural trends months to years in advance and wields staggering creativity in the collection of concepts, but struggles to choose menu items at a fast food restaurant. He has a plethora of clusters about the pros and cons of various dishes but makes no attempt to align all his awareness towards selecting the best one for his immediate needs.

Emlyn suggests that retrofitting my games to serve a “Mycroft” function would involve “clusters of facts arrayed around a single unknown, like the spheres of a model of the Copernican solar system” — the Copernican system in which the “single unknown” around which the planets are arrayed is in fact the sun, bright enough, my poetic education in symbolism tells me, that we cannot directly look at and see it… a great mystery, around or within which all things find their harmonious orbits…

A Copernican board, then, more to Mycroft’s liking, might look something like this:

For myself, it’s the motion of the moon around the earth that captures my interest.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, it transpires, had a game he played with friends. They would walk in the park, wittgenstein himself if I recall correctly, playing the sun, while one friend circled him as the earth and another circled the circling earth as its moon… I am told Wittgenstein particularly enjoyed this game because “nobody wins”…

**

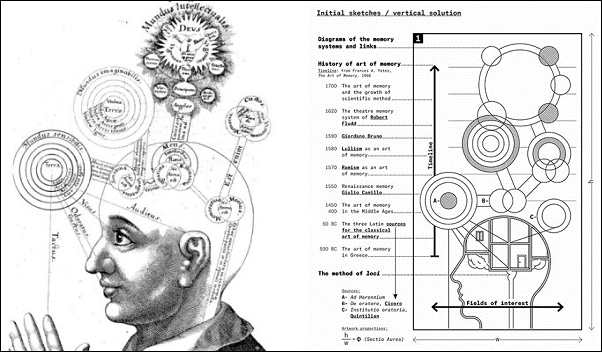

Next, Emlyn turns from the mobile and the solar system to the idea of memory palaces, which I discussed before in Sherlock Holmes, Hannibal Lector and Simonides — note again the Holmesian connection:

Where Mycroft’s memory palace is the resource of his conclusions, a place from which “The conclusions of every department” are culled and sorted, that he might be the governments “clearinghouse, which makes out the balance”, my Father’s is a resource unto its self, lending its exhibits from one massive wing to another in an ever evolving collection of antiquities, religious dictums, poetic verses and verdant projects, a spectacle to be appreciated, certainly, but not one intended to be the mechanism of an answer, rather there to be experienced and considered and revisited once a new article is catalogued or created for display.

Mycroft’s tidy and orderly “Central exchange”, an intellectual ministry, and my Father’s mental gallery are not parallel in architecture, but are laid with the same mortar and buttressed using the same alloys.

**

At last we turn to Sherlock himself — and to the issue of intelligence which is not only actionable but acted upon — and I think here of the shift by which an analyst (I’m thinking of Nada Bakos, as she describes herself in Manhunt) becomes a targeter…

It is at this point that we come to a final individual, Mycroft’s better known sibling, Sherlock. I have discussed my Father’s system of arranging connections, and outlined the underlying similarity of the mental mechanism Mycroft uses to synthesize an answer from his collected data to it, but, as my Father’s assembly does not reach conclusions, Mycroft does not solidify his suppositions through action, he defers his assessment to a minister who will choose whether or not to act upon it, or alternatively to his younger brother who will pursue the inquiry.

Sherlock said of his brother that “If the art of the detective began and ended in reasoning from an arm-chair, [Mycroft] would be the greatest criminal agent that ever lived. But he has no ambition and no energy.” It is not sufficient to reach a conclusion, one must be willing to “go out of [one’s] way to verify [one’s] own solution”.

In fact, of course — or should I say, in fiction? — Sherlock himself indeed arrives at conclusions, but he tends to have Lestrade around to execute them — to apprehend those Holmes has elicited confessions from or otherwise shown to be guilty. But Emlyn’s concern — to move from games of a non-actionable sort towards actionable games and thus, eventually, action — is well placed.

Indeed, it follows from the differing tempi of “pure” analysts and “practical” decision makers — or between strategists and tacticians.

**

Emlyn concludes:

Such a mental model as the one heretofore described can be of all the use in the world in reaping a creative crop or finding the hypothetical solution to any number of intractable problems, but without working out “the practical points” with the determination of the younger Holmes brother, all of it is for naught, and if the thought process is overlooked or limited by the consideration of the user, it is as inert as if its products were ignored entirely, its rewards as indispensable as Mycroft himself and equally as inactive.

It seems I have my marching orders: to devise a game whose tempo accelerates from a slower analytic periphery towards a high-tempo central insight, solution or target. An actionable game.

It’s a choice problem, and one that lies beyond my usual reach: I’ll set my mind to it.

**

Memory Palace diagrams:

Robert Fludd, from Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris Memory Palace exhibition at the Victoria and Albert

Related posts:

The Haqqani come to high Dunsinane Wei Wu Wei, or the inactionable option Sherlock Holmes, Hannibal Lector and Simonides Jeff Jonas, Nada Bakos, Cindy Storer and Puzzles Gaming the Connections: from Sherlock H to Nada B