Earlier this week I attended an event held by the Alfa Fellowship Alumni Association discussing Russian soft power. Panelists included John Brown, Jill Doherty, and Yelena Osipova.

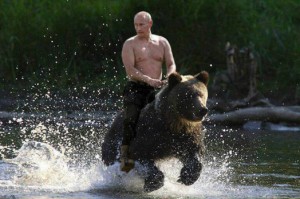

The question of Russian soft power arises against the background of the post-Soviet era, coupled with a decline in Russian hard power and the regrowth nationalist elements within the country. Noting that some have balked at the idea, Jill Doherty contended that to an extent, Vladimir Putin holds his own amount of soft power. There is some credibility to this argument, even in light of the questionable human practices under Putin’s leadership. In her comments, Osipova contended that Russia views soft power differently than the conventional definition coined by Joseph Nye.

I have argued before that Russia needs to “earn” soft power before it can be strategically utilized. But this does not appear to be the perception within Russia. Rather than seeing soft power as something that grows organically, Osipova’s presentation lent credibility to the perception that Russia views it as something that can, in a sense, be constructed and deployed. Many of Russia’s efforts in public diplomacy in recent years involve a type of advocacy, operating under the principle that by telling Russia’s side of the story better, that people will find its policies more agreeable.

This is similar to some American sentiments during the post 9/11 period, when a belief emerged in the United States that if America just “told its story better,” that it could ease some of the hatreds it faced in certain parts of the world. This however represents an oversimplification of public diplomacy, and neglects to incorporate the important aspects of listening and relationship building. Outlets like Russia Today and Voice of Russia Radio paint an unrealistically rosy picture of Russia and are a perfect example of this advocacy mentality, and are considered pure propaganda by many in the U.S.

And while many view soft power as an entirely “positive” concept, some soft power institutions can have a negative effect on perceptions of a government. For instance, throughout the Cold War, numerous ballet dancers defected from the Soviet Union to the West while on tour. It is a tradition of flight that continues to this day.

Overall, however, Russia’s view that soft power as something that can be physically exported has been demonstrated in its actions. While normally I might argue heavily against this because it leads many to misinterpret Nye’s original definition, I believe there is some credence to the concept.

A country’s culture, through methods of food, music, performance and more, is one element of soft power that can physically be exported and sent around the world. Industrial products like cars and technology can also influence audience perception of a country. But of course, the degree of influence these elements exert on foreign perceptions or actions is dependent on a variety of other factors. Plus, in order to have a positive effect, the product has to be attractive to begin with.

Looking farther back into Russia’s soft power history, one should also analyze the Soviet Union’s policy of exporting the Revolution. During the post-war period, and into the Cold War, this was enabled largely by one simple and affordable export that anyone could use with minimal training and maintenance: the AK-47. Enabling revolutions and supporting Soviet allies around the world, the AK-47 became a form of Soviet soft power in the form of a hard power export. The amount of goodwill that generated towards the Soviet Union is certainly debatable, but no one can deny that this hard power export was instrumental in supporting the Soviet policy objectives of opposing Western interests in conflicts and countries around the world. The attraction to this physical foreign export has been so strong, that it appears today on the flag of Mozambique.

Recognizing the soft power of physical exports in relation to the amount of influence they exert, we should also analyze how Russia has contributed, intentionally or unintentionally, to the events of the Arab Spring. More specifically, the climate change related 2010 Russian Wildfires contributed to a 40% increase in world food prices which undoubtedly increased the likelihood of protests in the Arab Spring countries. What could this realization mean for influence?

Certainly, many in the West look characterize Russia’s actions regarding the Arab Spring through the lens of its reactions to the military events in Libya, and its support for the Assad Regime in Syria. Yet if Russia’s strategic goal is to preserve the sovereignty of these nations and perhaps maintain the status-quo, one might wonder if Russia could have contributed to its strategic goals of status-quo stability by other means. Could Russia have stopped or otherwise hampered the Arab Spring in its tracks if it was physically capable of supplementing or manipulating its food exports in a way that decreased upheaval in these countries? Though this answer may not be entirely clear, it would be interesting to see if anyone in Russia is thinking along these lines.