by Dawn R. Gilpin

Israel’s deployment of social media, including a Twitter news conference over the Gaza situation, has been in the news lately. As an example of media response to these efforts in the U.S., the New York Times cited MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow as having “mocked” and “marveled” at the attempt to use such a structurally stunted channel such as Twitter, with its 140-character limit, to discuss matters of complex international diplomacy.

Reactions in the blogosphere have proven similarly unenthusiastic, even among champions of social media in public diplomacy. Writing for the Personal Democracy Forum at TechPresident, Nancy Scola acknowledged during the press conference that “Twitter isn’t proving to be a perfect medium for the Q&A.” Observers from the blogosphere to the BBC have described Israel’s communication program as “propaganda.”

There has been much discussion lately of how official state representatives or agencies are using social media for the purpose of public affairs and/or public diplomacy. We have repeatedly posted here about the growing social media effort of the US State Department, which has been using multiple platforms to inform the public and foster discussion of diplomatic issues. Individual State Department representatives such as spokesman Sean McCormack and Colleen Graffy are also active Twitter users who discuss State Department activities, live-tweet meetings and press conferences, and interact personally with followers. Jordan’s Queen Rania was one of the first prominent world leaders to use YouTube as a vehicle for public diplomacy. On the public affairs side, the incoming Obama administration has received considerable attention regarding its use of social media platforms, especially the web site change.gov, to keep the public informed of transition issues and solicit feedback and policy input.

Most of the coverage of these initiatives has been favorable, with both bloggers and conventional media lauding attempts by public administrators and elected officials to engage more directly and more transparently with their constituents. Writing for MediaShift, Mark Drapeau recently urged governments to ramp up their social media initiatives to improve the authenticity and legitimacy of their public communications, and to achieve greater success in branding campaigns. Why, then, has the response to Israel been so negative?

There are two main communication issues underlying this contrasting reaction. The first has to do with choosing the appropriate communication platforms for a given context and, even more importantly, using the chosen platforms appropriately. The other is related, but tied specifically to the ways in which we have seen social media are and are not well adapted for use in crisis situations. Strategic communication mistakes are costly in any circumstances, particularly when the stakes are high as they usually are in matters of public diplomacy and public affairs. Communicators need to evaluate the symmetry of communication exchanges, the culture of the social media context chosen, its structure. It is also important to consider the type and depth of information to be shared, particularly in crisis situations. In conducting its Twitter news conference, Israel unfortunately missed the mark on all four counts.

Personal Media Meet Social Media

Matt Armstrong wrote favorably of the steps taken by the US State Department to engage citizens via multiple social media channels:

Fostering engagement, creating transparency, and humanizing the “machine†all work toward building trust and legitimacy. [. . .] To do this requires reconceptualizing the utility and value of information, breaking the barriers preventing the effective use of information, and encouraging engagement.

“Engagement” is the key term here, and it strikes at the heart of social media. Any communication tool can be used in a variety of ways, but the point of many online services is to provide a space where users can actively participate in the conversations of the community. While all forms of media can be used to share information, not every type of information is suited to every platform, and not all forms of engagement are created equal. Failing to recognize the structural and cultural constraints of different social media tools can backfire. Instead of transparency and humanization, the impression is one of deliberate obfuscation.

In a recent article in New Media & Society, Marika Lüders re-examined the distinction between interpersonal and mass media in light of new communication technologies. As the line between media producers and consumers continues to blur, she argued, it becomes increasingly difficult to apply absolute labels to specific platforms without also examining their content and how they engage users. She proposed evaluating mediated communications along two continua: the degree to which they are formal or professional in nature, and the degree of symmetry. The more professional and asymmetrical the content and relationship between the communicators, the more “mass” the medium, whereas personal media are characterized by more symmetrical, less institutionalized relations.

This is a useful framework in which to assess the Israeli public diplomacy campaign, particularly the Twitter news conference.

The Structure and Culture of Twitter

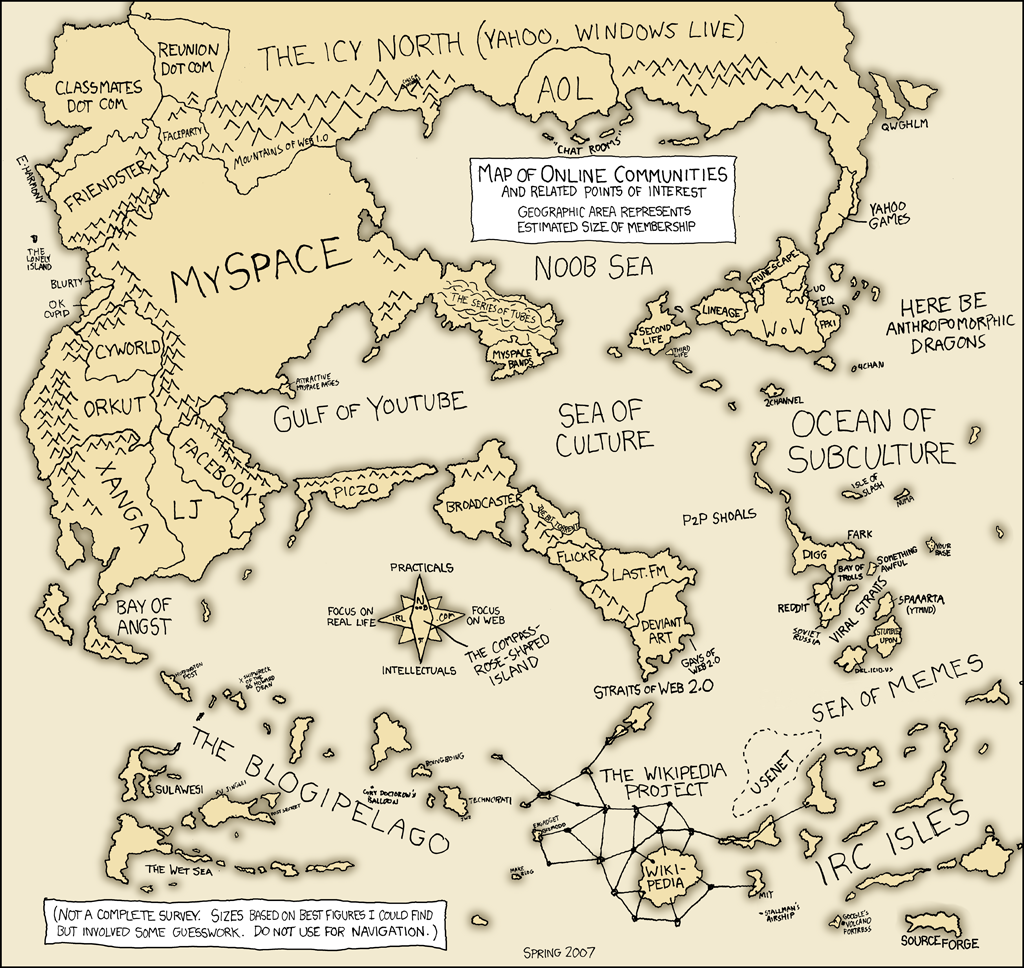

There are many cultures and subcultures active online, not just specific to certain tools, but also to particular communities of users. The XKCD cartoon below shows a humorous take on the vast range of cultures that exist throughout the Internet, and these cultures are constantly shifting and changing. (For instance, Twitter has created a whole new continent of users missing from the map–or perhaps a Gulf Stream-like current flowing through and past the Blogipelago.)

To use these tools effectively for strategic communication, governments (or any other users) must be familiar with the culture that predominates among the target audience. Context is essential.

For example, a blog can be an extremely effective tool for crafting a message and disseminating it to a large number of people. It is expected that a blog post will reflect the author’s point of view, and the format of the medium offers ample space to explain even complicated concepts. The commenting functions available on most blogs allow readers to express their opinions and ask for clarification, although the lack of threaded commenting and the post-centric structure of blogging mean that ongoing conversation is unlikely or at least somewhat difficult. Moving beyond text, YouTube or other video sharing services (such as Vimeo, GoogleVideo, or Imeem) allow for all of the visual and aural complexity of a personal appearance, which also make it possible for effective speakers to connect with viewers quickly and powerfully. The relationship between content producer and the reading or viewing public is two-way, but remains largely asymmetrical. The emphasis remains on the “host” of the blog or YouTube channel. Regardless of whether the blog content is more personal or professional, this asymmetrical structure creates a bit of distance between the blogger and readers, pushing it toward the “mass” end of the media continuum.

Twitter, on the other hand, has an entirely different structure and culture. As a tool, it can be used in a number of ways: to post brief updates throughout the day; to “live-Tweet” an event as it unfolds; to share links (for example to news sources, or one’s own blog post); and to converse with others. Twitter is like a crowd, milling about, sharing tidbits: a user might pause to engage in conversation with one or two others before moving on to continue mingling. Blog posts can remain current for weeks (or longer–see Steve Corman’s recent report of some of the most popular COMOPS posts, some of which date from over a year ago). Individual micro-posts (“tweets”), however, are ethereal in nature, as the Twitter “stream” flows inexorably forward in time, rarely referred to in the past. Content aside, Twitter’s naturally more symmetrical nature makes it more “personal” than “mass” as a medium.

Seeking to contain the Twitter stream to the format of a press conference is problematic–not only because of the structural limitations which, as the New York Times article cited above points out, forced the Israeli consulate into textspeak answers such as: “We hav 2 prtct R ctzens 2, only way fwd through neogtiations, & left Gaza in 05. y Hamas launch missiles not peace?” It also uses a short-term, symmetrical form of participatory media to conduct an inherently asymmetrical exchange. This conversation did not suit the participatory culture of Twitter, projecting the impression that Israel was more interested in disseminating its message than in engaging in open public discussion. Compounding this impression was the fact that, as Nancy Scola noted, the Consulate neglected to use the conventional @user response format to indicate to whom their comments were addressed (probably to save some precious character space in Tweets). The resulting effect was less of a conversation, and more of a podium speech. Which may, in fact, be appropriate for a press conference, but is yet further evidence of why Twitter was the wrong medium to use in this crisis.

Emergent vs. Top-down Crisis Communication

Speaking of crises, Twitter has been in the news a few times recently as a killer app for crisis communication. From the Mumbai attacks to a Continental Airlines plane crash, users shown Twitter to be a useful tool for live-from-the-scene eyewitness reports and information sharing. (This is the same capability that led the U.S. Army to warn against the dangers of terrorist use of the microblogging service.) This kind of rapid, emergent information sharing is where social media tools shine.

Professionals are also urging organizations and public agencies to adopt social media for crisis communication, and some–such as the Los Angeles Fire Department and the International Red Cross–are doing so. But there is a difference between using Twitter or similar tools to give up-to-the-minute, accurate information about an unfolding crisis, especially concerning matters of public safety, and seeking to use those same tools to explain complex issues. Tweets are essentially headlines, and while a series of short texts can be useful when no further information is yet available, any public diplomacy effort is going to require more in-depth analysis than can possibly be contained in any number of headlines. In addition to its failure to engage in symmetrical conversation with Twitter users, the medium itself was poorly suited to the context.

An Unintended Message of Inauthenticity

Taken together, the issues described here produce the impression that the Israeli government is seeking to control the conversation about the Gaza crisis in the wrong way. The New York Times quoted David Saranga, in charge of media relations for the Israeli Consulate in New York, as saying “I speak to every demographic in a language he understands [. . .] if someone is using a platform like Twitter, I want to tweet.” While it makes sense to reach out to varied audiences, the charge of propaganda comes from the fact that Israel has not used these new tools effectively. Just because a government has access to the hammer of Twitter and YouTube, doesn’t mean that every situation that arises should be viewed as a nail. If you’re going to tweet, you have to make sure to do it right.

Holding a press conference via Twitter is inappropriate because first, it uses what is normally a highly interactive, conversational, and ethereal medium as a message vehicle within a controlled time frame, and second, it eliminates all possibility of nuance in a highly complex situation. It would have been far more effective to use Twitter for brief updates about the crisis, and responses to short requests for clarifications. The Israeli Consulate could have then conducted their press conference via YouTube to address the public in a more personal manner, both by making a formal statement and responding to queries submitted via Twitter or YouTube. In this way they could have taken advantages of the strengths of the different platforms, respected the media culture of their intended publics, and also maximize the impact of their message without appearing condescending or out of place.

The lesson here is that social media can be used for effective public diplomacy, but only if those in charge of such efforts understand questions of symmetry, culture, and structure of the different platforms. Failure to do so produces the opposite of the desired effect: communication is seen as inappropriately controlling, out of place, and ultimately inauthentic.